The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (“Act”) was a “tipping point” in healthcare that set in place an aggressive path toward more “managed care” by implementing fixed-price payment rates. In 1997, the only thing for certain was the belief that community hospitals could not survive long term with the traditional patient models and that “change” must occur.

Up until 1997, cost-based reimbursement had been the paradigm for hospital payments. The BBA was a radical departure from this paradigm and an abrupt change. Neither hospitals nor consulting vendors had experience with using conventional improvement methods with these new challenges that BBA presented. Limited success with these initial experiences led many to believe that hospitals were so unique that the traditional performance improvement tools could not work in hospitals.

It is true that the hospital business model and its operational processes are unorthodox and complex. These hospital practices and processes, along with the information systems that supported the cost-based payment model, were not suited to this fixed-price reimbursement model. The improvement methodologies alone were not sufficient. The success of improvement methodologies required that the unorthodox and complex processes be redesigned first; however, redesign did not happen. Hospitals continued to operate as they had for the many years prior to 1997.

The only place to look was to the government to solve this problem, or more accurately, we hoped the government would reverse itself and raise rates again. Instead, the actual changes that occurred were hundreds, if not thousands, of “tweaks” around the edges of the existing model.

These tweaks were nothing more than “repackaging” of the same stuff in the form of new guidelines. Hospitals have spent millions of hours continually making changes to respond to new regulations. The net effect of these “tweaks” has been highly disruptive. They have consumed a significant amount of time that turned out to be nonproductive.

Then the direction shifted to spending billions of dollars to implement Electronic Medical Records (EMRs). To add to the financial misery, we have now paid billions of dollars to consume more of doctors’ and nurses’ time, made it more difficult to share information, lengthened length of stay in the ED, reduced customer satisfaction, and introduced more medical decision errors and added risk.

Commercial insurance did not want to take the initiative in the early years following 1997 to redesign healthcare. They followed the same general pattern of change initiated by the government to the point that commercial policy and structure for setting rates are essentially the same for commercial and government.

The Current Picture for Community Hospitals

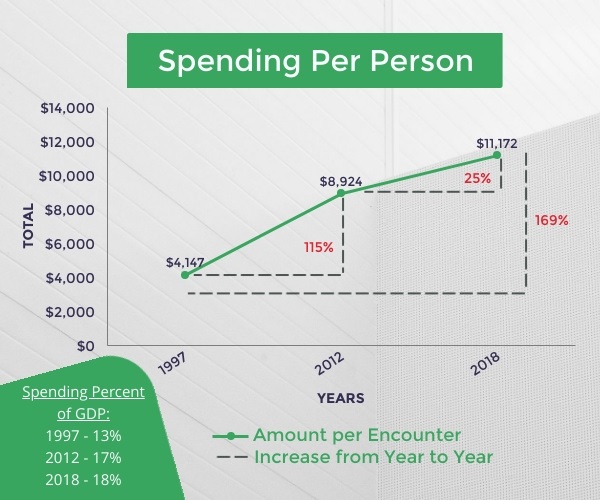

Healthcare spending has continued to increase.

Did Any Community Hospitals Win?

Winners Since 1997: Tertiary Hospitals

- Hospitals have grown financially strong.

- Dominate urban and suburban markets.

- Have eliminated competition.

- Have reduced access and options.

- Driven prices up an average of 6%.

- Quality has not increased.

And the Losers Since 1997: Small Community Hospitals

- Continue to struggle financially.

- Many SCHs have been acquired.

- SCHs acquired have lost services, access, and independence.

A primary argument for tertiary hospital acquisition of SCHs is that the tertiary hospital would be more efficient and provide better services and greater access to a small community. This has not been proven true. And many tertiary hospitals have seduced communities into giving their local hospital away. Most SCHs acquired by tertiary hospitals have been turned into local clinics. And access and convenience has declined and others closed to eliminate competition. Very few promises have been kept. And rather than reduce spending, prices have been driven up by an average of 6% and quality of care has not increased following acquisition. (Melanie Evans, Wall Street Journal, 01.01.20)

I am familiar with a common practice in which tertiary hospitals acquired CAHs as purely a “smoke and mirrors” balance sheet transaction. For example, one particular tertiary hospital bought five struggling CAH hospitals within a 50-mile radius. The tertiary hospital turned a $5 million loss for all five into a $7 million profit for the group of five CAHs (a swing of $12 million) by taking advantage of the “cost reimbursement” features of CAH hospitals. These CAH hospitals are now “clinics” and feed the tertiary hospital, and are left with one primary care physician and a nurse. But the community has to now travel 30 to 50 miles for the same patient care they previously received locally. I would say the local hospitals lost.

Acquired have lost the battle, and are losing the war.

What Went Wrong?

There are two forces that drive and control spending – the open market (economic) and government (political). Each has a separate, distinct role. The government’s role is to solve the political problem. And the market’s role is to solve the economic problem. We have the wrong expectations of who should solve this problem, and we are now turning the wrong handle.

The government has a mandate to reduce spending, not to preserve the community hospital. And certainly not to ensure SCHs’ future by reversing itself and increasing reimbursement rates. Since the government must keep all financial changes “budget neutral”, the government is limited to setting policies and rates for the substantial part of the net revenue (often over 50%) it pays to hospitals. This means it cannot increase the total dollars in the aggregate it pays annually. It simply moves money from one bucket to another.

Sadly, we have relied on the government for over 20+ years hoping it would reverse itself and again raise reimbursement rates. But the government does not have the authority, the financial resources, nor the political will to solve this problem; and market economics restrict commercial insurance and hospitals from increasing payments.

What Does This Mean?

It means that community hospitals have not improved their financial condition in real terms, and as time passes, operating losses continue and customer service, access, and the scope and quality of medical services are declining. This deterioration has raised questions by many parties as to the long-term viability of the community hospital. In 2012, 15 years following 1997, an article in Becker’s Hospital Review asked the question “Is The Community Hospital a Dying Model, or Is It the Future of Healthcare?” (beckershospitalreview.com, May 30, 2012)

ANSWER: As of 2020, many Community Hospitals are dying, and are not currently in the position to be the Future of Healthcare.

Think about this. One would think that after 15 years of the BBA, we would have made more progress. Not so. And even in 2018, 21 years after the Act, we have not made significant progress.

What Are Hospitals’ Options?

As with all business transitions, the effective long-term solution attacks the fundamentals of business. One doesn’t have to look far – automobiles, steel production, manufacturing, technology, communications, transportation, banking, and on and on.

The good news for hospitals is that the government currently sets rates for most SCH services based on the actual national costs to operate hospitals. If this method continues, SCHs can be assured of success by becoming low-cost providers. The low-cost provider will always be profitable. And the more effective one is about being low cost, the more profitable it will be.

I worked at Delta Air Lines prior to the government deregulation of the airline industry. At that time, the federal government set all airfares based on the sum of all operating costs of all airlines. At that time, Delta was the only carrier that did not have a union. And Delta was very, very efficient. This resulted in Delta making huge sums of profit for many years when many of its competitors were struggling and many bankrupting. It was common knowledge that Delta couldn’t lose money if it tried.

This puts control of the SCH’s destiny in its own hands. This is also good news… if there is someone that knows how to redesign hospital processes and apply improvement tools and methodologies to achieve “low cost” under these conditions. So where do SCHs look for solutions, and how do they become a low-cost provider?

Performance Principle

Let’s start by understanding what “low cost” means – and with an important caution. An effective “low-cost” provider is not one that simply cuts its costs arbitrarily. In fact, cutting costs arbitrarily is worse than doing nothing, and leads to degradation in services and then to decline in revenue to eventual closure. This cycle of service-revenue declines becomes a downward spiral that continues from which one cannot escape at some point.

A successful low-cost provider understands the principles of high performance. The high-performance theory says that there are two dimensions to performance. Processes must be designed for both dimensions, and as performance needs to be improved, both dimensions must be considered.

If applied correctly, both efficiency and effectiveness improve concurrently with design and improvement. Efficiency is improving the financial contribution or profit margin of delivering the service. This says nothing about “cutting costs”. And effectiveness is improving the quality of the service, delivery, or how accessible, how well (satisfaction or satisfying), and quick service is delivered. Both efficiency and effectiveness improve concurrently if methodologies are used correctly. Effectiveness doesn’t suffer from improvements in efficiency. Nor is efficiency sacrificed as the service quality is improved.

These performance improvement tools in the non-healthcare, commercial world have always worked and is the reason that manufacturing and service industries such as Amazon provide such a high-quality product or service at low costs. You may recall Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle adopting the performance improvement methods of Toyota to achieve improvements. If you read the literature carefully you would have seen references over and over to “redesigning processes” as inherent to improvement.

Not all attempts worked; but not because the tools don’t work. The tools work. Rather many of these methodologies were misunderstood and misapplied. The missing link from manufacturing to hospitals is understanding how to analyze unique hospital processes and apply the tools and techniques to the unique nature of hospital patient care.

Our core competency is the application of the proprietary performance improvement methodology CATALYST™ that we have developed specifically for community hospitals. See examples of the successful application of our methodologies, and the magnitude of the benefit. All of these improvements occurred through the application of principles of performance used in other industries.

Your Enemy is Time, Not Money

So, financial distress doesn’t have to happen. Financial losses and closure do not have to happen. Year after year of losses and erosion of services does not have to happen. Attacking the business fundamentals is the only solution. You may ask, “Do I have enough money to become successful?” My answer is your enemy is time, not money. You can become successful by improving your cash flow concurrently while making investments. The question is: are you running out of time?

The population of most small community hospitals is more than sufficient to generate significantly more revenue from both intercepting outmigration and increasing services. Next, learn to employ performance improvement tools and techniques to redesign patient care processes that improve both the efficiency and effectiveness components of performance.

Commit to it, learn how to use it, and attack the fundamentals of business. Finally, apply these lessons to keep inpatients local, since they yield the largest profit margin of all services, and are the easiest, and fastest to intercept since most SCHs get only 20% of their market.

You can achieve growth and access, remain independent, and control the decisions locally. HospitalMD™ provides solutions to SCHs.

Community hospitals must make a transformation. SO, MAKE A TRANSFORMATION THAT ACHIEVES QUANTUM RESULTS, NOT INCREMENTAL CHANGE.

I would be happy to share our insight and examples of quantum improvements in success. You can reach me at either contact listed below.

Jim Burnette

CEO, President of HospitalMD

(770) 262-3169

jhb@hospitalmd.com